Over at the National Review, Andrew T. Walker has put together an interesting article called “Understanding Why Religious Conservatives Would Vote for Trump.”

In it, Walker grapples with the understandably popular question of why a Christian would support someone President Donald Trump, a man whose, as Walker admits, “career and persona typify all that religious conservatives have protested in American culture.”

It’s a popular question.

Shortly after the 2016 election, I myself wrote about how mystified I was by the 81 percent of white evangelicals who threw in for Trump, and there have been enough similar pieces written in the years since to make it clear I wasn’t the only Christian baffled by this capitulation.

Walker himself says he didn’t vote for Trump in 2016 and does not hint at his plans for this November. To his credit, he calls on religious conservative Trump supporters to be more objective in their reviews of Trump’s actions. However, Walker says he has “backed off [his] former insistence that a Trump vote means automatically surrendering one’s principles” and sympathizes with what he takes as these voters’ justification for their support. According to him, mainstream media has unfairly painted religious conservatives who voted for Trump with too broad a brush. He says these voters collectively “approach politics with far more complexity and internal tension than journalists claim,” honing on abortion as a “morally transcendent issue” which religious conservatives won’t budge on.

“Anyone who wonders why religious conservatives cannot bring themselves to vote for Democrats simply does not understand the religiously formed conscience that shudders at America’s abortion regime,” Walker writes. “Religious conservatives are faced with the undesired situation of choosing between two alternatives: a compromised, unqualified figurehead, or a disastrous policy platform that bears the marks of intrinsic evil, such as abortion.”

So Walker’s claim is relatively straightforward. Christians who voted for Trump have a few moral litmus tests and Trump passed. Contrary to Walker’s claim that these voters are approaching politics with complexity, this actually seems fairly simple. Religious conservatives were caught between a rock and a hard place: Trump or a pro-choice candidate. They went with Trump.

There are a few problems with this framing. The first is that religious conservatives did not face a binary choice of Trump or Clinton in 2016. In fact, the Republican Party offered a large number of qualified candidates in the primary, all of whom opposed abortion and claimed to be Christian. From Senator Marco Rubio to Senator Ted Cruz to even well-funded “Washington outsiders” like Dr. Ben Carson and Carly Fiorina, there was no shortage of viable options. Religious conservatives are the bulwark of the Republican party. Half of all Republicans say they are conservative and either highly or moderately religious; they are the most reliable voting demographic in the country. They would have gotten an alternative to Trump if they’d demanded one.

The second problem with this analysis is that it ignores the non-white religious conservatives who didn’t vote for Trump — particularly people of color. Walker characterizes critiques of these voters as the “scorn religious conservatives receive from secular and religious elite” but that discounts the fact that this scorn is also being leveled by plenty of voters far more disenfranchised than white evangelicals.

Black Protestants tend to be religiously conservative, but their support for Trump has hovered around 12 percent for the entirety of his term. In Walker’s framing, are Black Protestants simply apathetic about the so-called rise of secularism? Or is there a level of racial ignorance that his analysis fails to take into account?

The final issue has to do with polling trends. Walker makes it clear that his article is anecdotal, noting that “statistics do not, and cannot, capture the complexity of religious conservatives.” That may be, but he also theorizes that “the vast majority of religious conservatives only reluctantly support Trump”, so at some point, we must invoke what data we do have. And that data says that for most religious voters, abortion simply isn’t the single issue for religious voters Walker thinks it is.

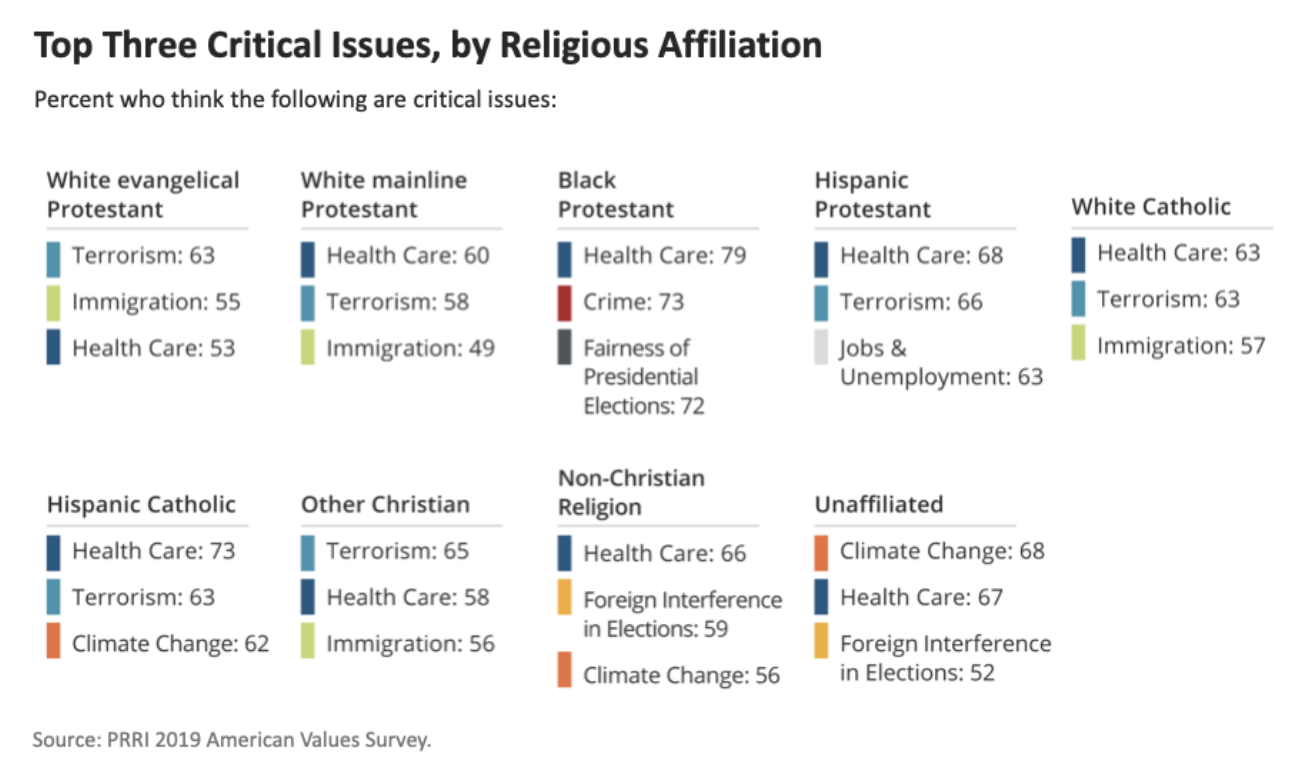

This PRRI poll is only the most recent study to find that the policy concerns of white evangelical and mainline Protestant voters aren’t all that different from the electorate at large. Abortion doesn’t even crack the top three.

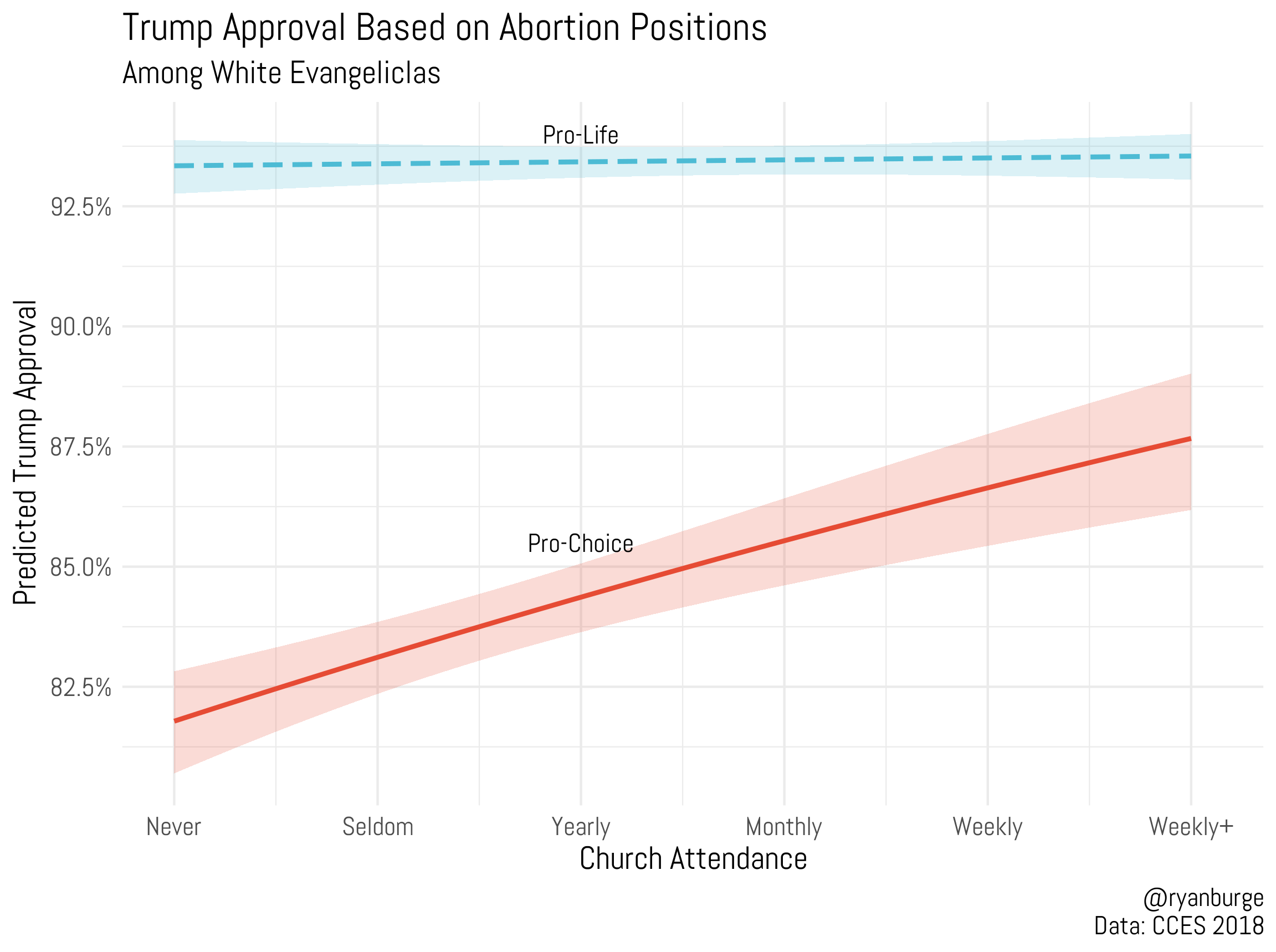

There’s another problem with Walker’s theory. If abortion were a primary reason religious conservatives held their nose and voted for Trump, you’d expect to see a sharp drop in his support among pro-choice evangelicals. Instead, as Ryan P. Burge notes, there’s hardly any decline at all. Pro-choice white evangelicals approve of Trump in high numbers that only get higher the more often they attend a religious service.

So Walker’s explanation may explain the voting habits of his friends, who he insists are internally strained by their vote, but it just doesn’t add up with what we know on a larger scale.

Polls show that white evangelicals not only voted for Trump but continue to rate his job performance highly. Walker says “[n]o religious conservative I know does not wince, grimace or eyeroll at many of President Trump’s actions” and that may well be, but wincing, grimacing and eyerolls are meager comfort for refugee children detained at the border, officials fired for testifying or Christian refugees no longer allowed to seek asylum in the U.S.

When cable news is filled with people like Jerry Falwell Jr., Ralph Reed, Paula White and Robert Jeffress, one can’t help but wonder just how representative Walker’s social circle is of religious conservatives in America at large. After all, the rows and rows of MAGA hats at this year’s March for Life suggest a far more enthusiastic marriage between Trump and religious conservatives than he theorizes.

“Those who hope to sway voters away from Trump through endless berating think pieces will fail,” Walker writes, and he’s probably right. This article isn’t going to change any Christian’s mind. At best, I’d like for a little more honesty about why they voted the way they did, and for the rest of us to consider an alternative theory that seems to square the religious conservative support for Trump more easily than Walker’s.

Falwell, the Liberty University president who has been one of Trump’s most outspoken Christian supporters, has repeatedly praised Trump for his moxie. It’s probably Trump’s most famous character trait: his willingness to unleash on any defection with maximum impact. Likewise, Jeffress told then-Washington Post reporter Elizabeth Bruenig that “most Christians I know see the election of Donald Trump as maybe a respite” from a culture they feel wants them to just go away. After decades of putting hope in conservative politicians like President George W. Bush to reverse their fortunes, white evangelicals are ready for someone who punches back on their behalf.

In this framework, Trump’s coarseness is a feature, not a bug. The cheers at his rallies, the defenses of his crudeness, the hundreds and thousands of gleeful retweets of “go back where you came from” are not the actions of a conflicted coalition who chose the lesser of two evils, but a base grateful that someone is standing up to what they see as unfair treatment from the broader culture: secularism, “the media”, “liberals”, “the elites”, what have you. As Bruenig writes:

“By voting for Trump — even over more identifiably Christian candidates — evangelicals seem to have found a way to outsource their fears and instead reserve a strictly spiritual space for themselves inside politics without placing evangelical politicians themselves in power. In that sense, they can be both active political agents and a semi-cloistered religious minority, both of the world and removed from it, advancing their values while retreating to their own societies.”

Maybe this is how Trump won in 2016. Maybe it’s how he’ll rally white evangelicals to win again in 2020. Trump can do and say the things to the evangelicals’ perceived foes that they themselves can’t or won’t. He can engage in acts of no-holds-barred aggression that his more character-minded supporters are too morally upright to entertain. He is the gun they’re bringing to the political knife fight.

Trump voters often point out that there are no perfect candidates. That’s true, and Christians are hardly the only voters to wrestle with that fact. Every participant in any democracy makes a few concessions when they cast a vote. The trick is having the moral clarity to know what concessions you’re willing to make and why. In this sense, principled voters who hail from the Christian Left, the Never Trump Right, Black Protestant Churches or any other Christian demographic are no less nuanced than white evangelicals who voted for Trump.

The question white evangelical Trump supporters must ask themselves is what issues they’re actually championing when they vote for Trump, and whether the concessions they’ve made are worth the cost. If it is indeed to score a few wins for religious conservatives on social issues, then the bargain has been a messy one at best, since Trump has advanced as many cruel and inhumane policies as he has anti-abortion efforts. But if the real goal, as I suspect, was nearer to giving religious conservatives a real fighter who could escalate political discourse to winner-take-all bloodsport and win on such terms — to own the libs, you might say — then they’re getting their money’s worth, as high as the cost might be.