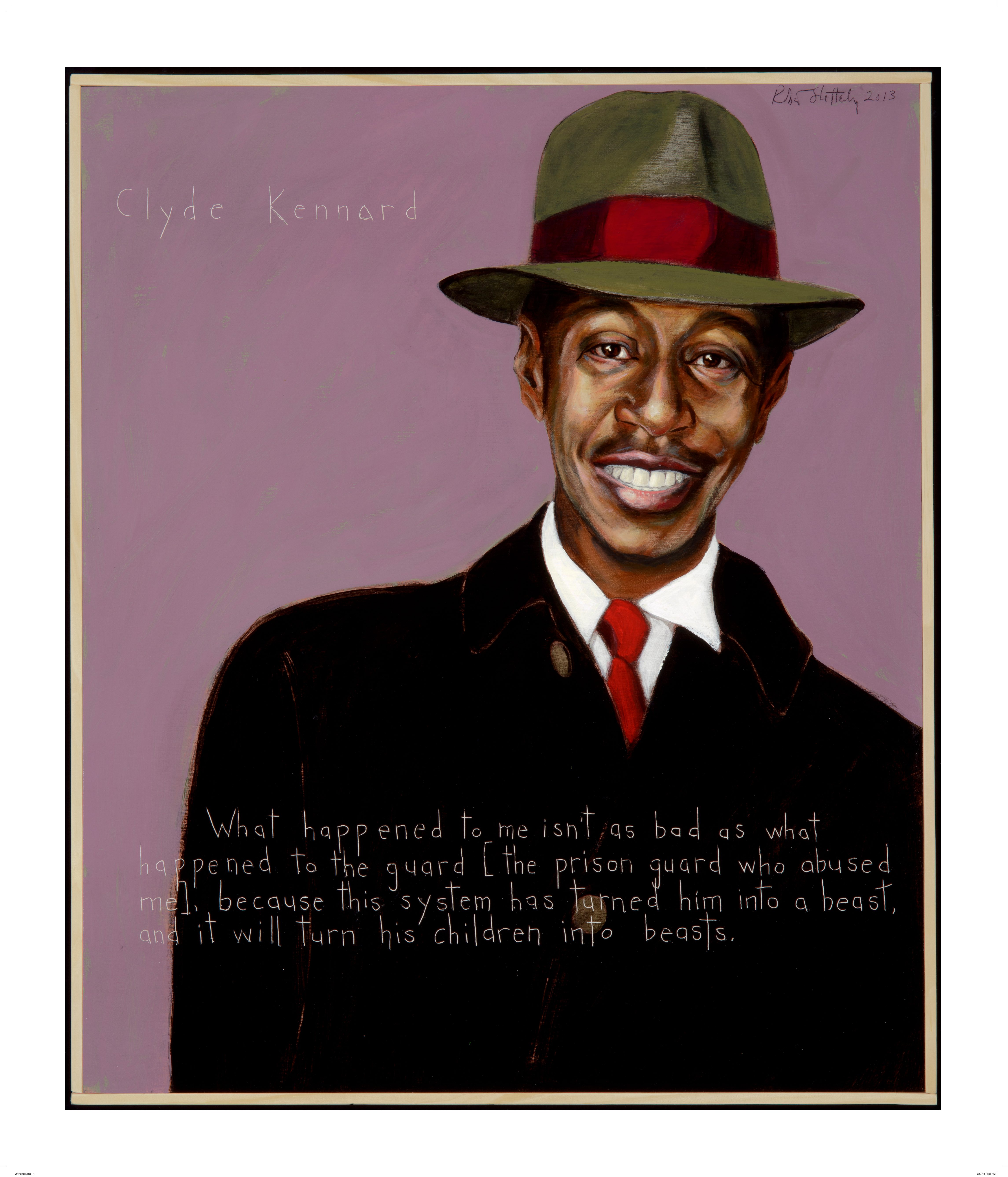

Clyde Kennard taught Sunday school at the Mary Magdalene Baptist Church of Hattiesburg, Mississippi. A year prior, the decorated veteran had returned after serving seven years in the Korean War to work on his bachelor’s degree at the University of Chicago. But after three years of a political science major nearly finished, he left Chicago and moved home to take care of his mother who needed help on the family farm. Kennard wanted to finish his education, but the only college in the area was the all-white Mississippi Southern College that denied his attempts to apply on three separate occasions.

Despite repeated roadblocks and failed attempts to discredit his Christian character, he remained undeterred until framed for stealing $25 worth of chicken feed. After a 10-minute deliberation of an all-white jury, he was sentenced to the maximum seven years with hard labor to be served on the prison’s cotton field. He was later exonerated of the charges; the key witness recanted, admitting the intention to bar him from college. Yet while incarcerated Kennard became ill with what was much later discovered to be intestinal cancer. Prison officials refused to treat him, release him or let him do his time without the hard labor. After protests, the terminally ill man was finally released.

But it was too late.

He died six months later, without bitterness for his grave injustice, but a last lament for his persecutors on his lips:

“I’d be glad [this evil] happened if only it would show this country where racism finally leads,” he told journalist John Griffin. “Be sure to tell them what happened to me isn’t as bad as what happened to the guard (who verbally abused him on the ride to the doctor) because this system has turned him into a beast, and it will turn his children into beasts.”

Clyde Kennard died on July 4, 1963 at the age of 36. After his death, Griffin asked his mother, Leona Smith, “How can we stand it? This isn’t America. This is Dachau and Auschwitz. This was a man who had great things to contribute, and because he wanted to finish his education in an area where he had every right, where his tax dollars supported the school, he was thrown to the mad dogs and ended up a martyr.” Smith made no reply, but Griffin recalled, “[T]he deepest grief I have ever witnessed was etched on her face.”

Clyde Kennard died a victim of hatred and bigotry more than 50 years ago.

Earlier this month, in Charlottesville, Virginia, more victims for the cause of justice and equality were added to the grim list of casualties of racial hatred in this country. Many on social media and news outlets have condemned the attacks as anti-American. Many expressed surprise and disbelief at the blatant alt-right hatred on display in the streets of Charlottesville. But there were many who were not surprised, and this difference in reaction is worth consideration. At the rallying of hatred and the uniting of racist voices, people of color are not stunned. They are altogether aware of the persistence of racism and the terrain it occupies in this country.

While the condemnation of the events in Charlottesville as un-American may well be uttered in an attempt to shore up victims and express unity and hope, it pronounces a memory that some of our neighbors simply cannot access, a description that historically does not ring true. In the utopic sense of the word, of course, there is nothing more “American” than a decorated war hero with a determined spirit toward higher education and service to the Church. As the stack of official condemnations grows, we might consider the narrative on which our dissent rests. For to condemn the cancerous display of hatred as un-American is to silence the stories of fellow neighbors, fellow brothers and sisters in Christ, whose laments cry out to the contrary.

Yet there is an opportunity here, long after media feeds have quieted and #Charlottesville is no longer trending. Because we can, and we must, condemn injustice, racism and white supremacy as altogether anti-Christian. The evils of racism and the systems and stories it perpetuates among us are entirely counter to the gospel we proclaim. As the Church, we need to be clear that we bring no qualifiers to that statement, no add-ons, nothing else in our hands. We simply profess Christ, who, in his own vicarious humanity declares all human worth. To offer anything else is to risk further silencing our neighbors and the one in whose image they are made.

I met Natasha Oladokun at an arts conference in Richmond, Virginia in February of 2017. We were both speakers at a symposium that sought to explore the gift of the arts and the spirit of Christian mission. When she read her poetry aloud, my eyes kept trying to blink her age into focus. How was it possible so young and clear a voice could carry such a heartbreaking and heartbroken cadence—and yet somehow offer it as prayer? A graduate of UVA, Oladokun lives and writes in Charlottesville, Virginia.

She writes:

Chief among my many worries, living in and with this body, is that fatigue will simply become a way of existence for me. I worry that the two things in my life that have staved it off the most: my faith in Christ, and poetry—which I’ve described elsewhere as my rickety bridge from desolation to the divine—will eventually crumble like dust underfoot, and that I will lose hold of both tethers that have anchored me thus far. I am so tired, I keep hearing myself say.

Like the disciples in the garden of Gethsemane, my own weariness suddenly seemed so indulgent, so unjust—while Christ was sweating blood in prayer in the shadow of evil. My neighbors of color were keeping vigil beside Him, adding their own sweat and tears to the body of the one who carries it all to death on the cross. I am so tired, I keep hearing myself say.

For the weariest among us, Christ’s call to stay awake and to get up is a kind and dignifying affirmation that He sees and knows the deepest of griefs—and that He, too, grows weary of the heavy eyelids and indulgent apathy that threaten to keep friends unaffected by stories of evil in their very midst. As we pray for Charlottesville, might we also pray for the strength and courage to stand awake in a community of lament, bringing our anger and our protest, our sorrow and our neighbor’s sorrow before the God who promises to collect our tears in his bottle.

For Natasha Oladokun is not alone in her weariness. She is in the company of many who share her lament, who are so tired, who are worried and afraid, who pray and lament in ways that are never easily put to bed or silenced by an eventually quieted newsfeed. Condemning the gross display of white supremacy and alt-right nationalist hatred in Charlottesville with Twitter feeds and official statements and eyes half-closed is easy.

Denouncing racism and injustice wherever they rear their vile heads the next time and the next time and the next time is expected and undemanding. Lamenting it with our eyes really open, with ears willing to hear the differences between my white reaction and that of neighbors who are reacting differently, with hands and feet willing to the embrace the weary, with hearts willing to join in the same blood soaked prayers—this requires so much more.

But isn’t this exactly what Christ asked of His friends as He peered down the wearying minutes that brought Him closer to bearing this very evil on His own shoulders, dying to carry its cancerous grip out of our hearts, out of Charlottesville, out of this world that is not the way it’s supposed to be?