The United States has seemed oddly immune to the huge growth of religious skepticism over the last half-century. That perception changed two years ago when an American Religious Identification Survey noted the number of Americans who profess Christianity fell sharply from 85 percent in 1990 to 76 percent in 2009. Perhaps even more surprising was the surge in those who claimed no religion: The number nearly doubled from 8 percent in 1990 to 15 percent in 2009. In his April 2009 Newsweek article, “The End of Christian America,” Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Jon Meacham suggested America had begun its encounter with an “old term with new urgency: post-Christian.”

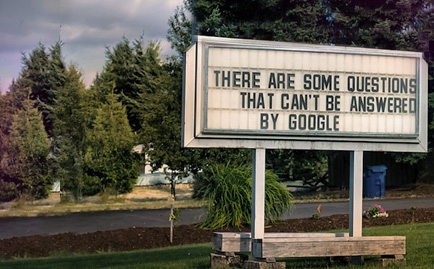

“What has changed everything?” Christian apologist Josh McDowell asked his audience on July 15 at the Billy Graham Center in Asheville, N.C. His talk, titled “Unshakeable Truth, Relevant Faith,” had detailed a certain uncomfortable fact in anticipation of the question: that young Christians in America are rejecting Christian fundamentalism—and doctrinaire concepts such as absolute truth and biblical infallibility—in droves. Why is faith in God being supplanted, earlier and earlier, by relativism, secularism and skepticism? McDowell’s answer was simple: the Internet.

Of course, his response touched off an immediate flurry of online activity—much of it from skeptics. “Does he or does he not think Christianity can win in the marketplace of ideas?” one atheist blogger asked. “Either you can handle the arguments or you can’t. You’re just whinning [sic] because you can’t.” The highest-rated responses to the story at The Christian Post, among the first outlets to pick it up, joined the gasconade:

“Christianity does poorly when it doesn’t control the entire message and allows people a free exchange of thought? What a freaking shock.”

“My prediction: look for theists to start withdrawing into Internet-free communes.”

Can the explosive growth of irreligion—that amorphous term comprising deism, agnosticism and atheism as well as relative neologisms like antitheism and ignosticism—really be linked to the Internet? Some atheists on the web seem to think so. A question in the forums for The Friendly Atheist, a popular blog among non-theists, asked whether ex-theists would have shed their religion if the Internet didn’t exist. Many felt they wouldn’t. A post on Unreasonable Faith (ostensibly a counter to Christian philosopher and apologist William Lane Craig’s book and online community dubbed Reasonable Faith) surmised that the Internet was crucial to the success of the “New Atheists.”

While Christianity enjoys a robust online presence, the edge still seems to belong to its unbelievers. ChristianForums.com, online since 1998, boasts a quarter-million members. But with an Alexa ranking of almost 12,000 in the U.S. and only 68,000 unique page views per month, it lags behind the most popular forums for the irreligious. The web’s largest atheist forum is a subcommunity of the social media site Reddit, launched in 2005. Its Alexa traffic ranking puts it in the top 50 sites in the United States with 2 million unique visitors per month, many of those to its “Atheist” subcommunity of 154,000. The Christian “subreddit,” a devoted group comprised largely of recovering evangelicals with a zeitgeist-oriented view of Scripture, enjoys less than a tenth of the atheists’ readership.

Other mainstays of the influential web 2.0 communities driving the meme-generating social news scene add to the trend. From subversive offerings like Digg and 4chan to the juggernaut of YouTube, all are either predominantly or increasingly anti-religious. The distressing question we’re forced to ask is not, “What has changed everything?” but, “Why?”

A Free Space

The fact is, a relationship between irreligion and the Internet was bound to happen. Religion has long enjoyed a culturally accepted free space in which to share rhetoric—the Church. Atheism has suffered the exact opposite. America’s wariness of (or its outright antagonism toward, in its greatest excesses) irreligion has forced atheism to the fringes of its society. What the Internet has provided is a free space for atheists in this nation to connect with those across the globe whose cultural milieus are more inviting of all brands of irreligion; indeed, some in which secularism is a majority viewpoint.

It is no wonder, therefore, that atheism is gaining steam in the U.S. Compared with the Internet, not to mention the secular nations of those with whom that space is shared, America is downright stifling. The political sway of the religious right seems somehow more maddening. The “we don’t belong!” rhetoric of American atheists becomes stronger, and it’s a message that today’s Christians buy into.

That’s because the free space in which they share rhetoric was never the Church to begin with. The Church belonged to their parents—the Internet belongs to them. The Internet may be helping to facilitate deconversion among evangelical youth, but it is not because of an “abundance of information” that challenges their faith. Rather, it is because the place where they spend much of their lives is where non-theists often control the discourse. It’s safe to say the majority of voices they encounter in web forums, news blogs and Facebook timelines will not echo those heard in their church foyer.

How will the Christian establishment respond? So far it’s employed much the same tactic it’s been using since the Jesus Movement: creating its own brand of popular culture instead of engaging pop culture at large. YouTube is too dangerous; try GodTube. Wikipedia is too liberal; use Conservapedia. Church remains the bubble in which rhetoric is exchanged; the bubble merely now extends to the web. The net result allows Christians to be “in the world but not of the world” and secularists to control the traffic flow on the largest thoroughfares of the information superhighway.

Sure, the reappropriation of secular pop culture resulted in a glut of success for evangelical Christianity between the ’70s and ’90s. For a brief period it made hit records, hip fashion, a few regrettable television shows and billions of dollars. Christian bookstores and radio stations were ubiquitous, offering family-friendly access to the latest trends, and the church was still the place where religion happened. But now that moment has passed, and the relative protection of its cultural landscape has been replaced by a more open, more liberal web-driven one. In terms of evangelism, the freedom provided by the web has made inroads in some of the least Christian corners of the globe, but its fast pace has left the American Christian—and her teenaged son—in its wake.

It is clear that Mondays and Wednesdays are no match for long evenings spent surfing the web. Yet the Internet itself, despite its breeding ground for relativism, is not the problem. For American Christianity to hold on to this generation, it will have to engage culture where it’s found and raise the level of discourse accordingly. A sense of ecumenism is crucial to foster the sense of inclusivity provided by the web.

Today’s Church is uniquely challenged to value its online presence as much as it values its physical building, serve its online community as much as it serves the local one. Ultimately the web has to become a place where—perhaps for the first time—disillusioned Christians can truly encounter Christ.