Margaret Atwood, author of the 1985 feminist dystopian novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, recently told People Magazine: “I decided not to put anything in [the book] that somebody somewhere hadn’t already done. But you write these books so they won’t come true.” You might assume the novel’s depiction of a totalitarian theocracy to be a sardonic, cynical reading of Scripture, but it’s more of a cultural critique showing the dangers of using decontextualized Scripture to gain political power, which is nothing new (just ask Martin Luther, or read Jesus’ rebuke of the Pharisees in Matthew 23). Atwood’s comments remind us The Handmaid’s Tale is indebted to the sins of our cultural past, as well as a warning of how those sins can revisit us.

In the oppressive patriarchal regime of Atwood’s fictional Gilead, there are strict class distinctions, but even the wealthiest women have little power outside of their prescribed gender roles. Handmaid’s contemporary America has experienced a plague of infertility, and in the absence of new life, society resorts to brutality and dehumanization. The secret commanders of Gilead instigated and won a war with America, constructing a class/gender system that disempowered any woman capable of childbearing. These women were enslaved as “handmaids” for commanders’ families, and in Gilead, they endure a regular rape ritual by their commander, presented as a religious “ceremony.”

In Atwood’s novel and the Hulu miniseries (returning for season three June 5), the trials of a handmaid are seen through the eyes of Offred, the handmaid of chief commander Fred and his wife, Sarena Joy. Offred’s cruel context invites numerous political and feminist examinations, but in an apocalyptic sense, The Handmaid’s Tale echoes our American past, reflects our present and prophecies our fears for the future.

Philosopher Michel Foucault understands modern Western society as a repressive prison system called a “carceral system.” He claims that the discipline enforced upon prison inmates via surveillance and punishment is a smaller, more extreme model of the larger cultural mindset. In a carceral system or society, “disciplinary normalization”—the process of how seemingly-intuitive and self-chosen cultural ideas of what is “normal” or “abnormal” become conditioned by higher authorities—often takes place. We are constantly judged, says Foucault, by “judges of normality”—teachers, doctors, social workers. We behave “correctly” because we know we are being watched, and we fear punishment if we deviate from the norm. In this sense, carceral systems mold society into a homogenous group, even if they still believe they are “individuals.” Foucault also claims that a “delinquent,” or one who deviates from the norm,” is an “institutional product.” Those judges of normality tell us who is good, bad, weird or “normal.”

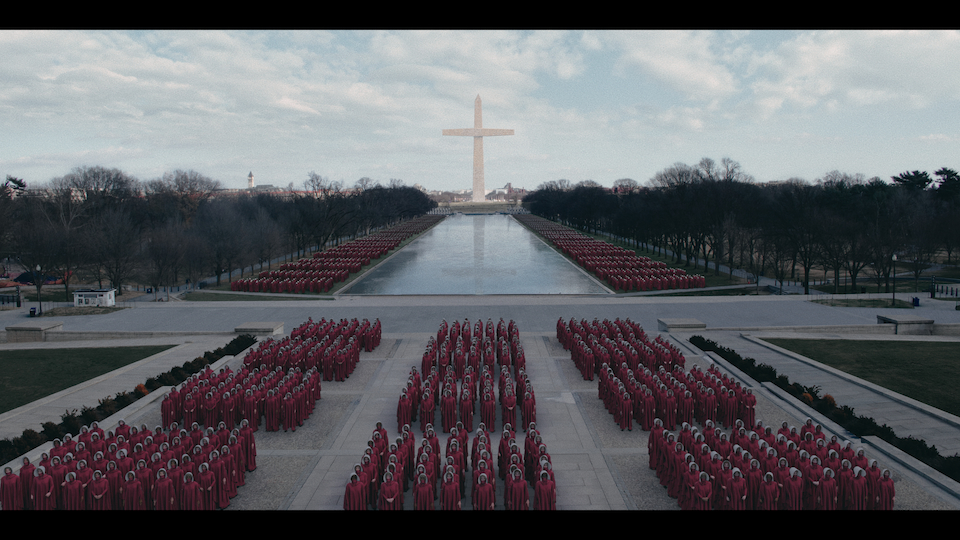

Foucault explains the mechanisms of the carceral system are often invisible to us. But the carceral system of The Handmaid’s Tale lays bare its workings. In Gilead, the women are “delinquents” because of their gender. The handmaids repeat a pat slogan—“under His eye”—as a reminder not of God’s care and provision but of their constant surveillance. They wear red garments to represent the blood of childbirth, as well as white hats with “wings” on the sides that prevent them from seeing or being seen. Any attempt by a handmaid to become an individual, by reading or wearing different clothes or even calling a friend by her real name, makes them delinquents. This morality is constructed by those who hold power, and the handmaids are forced to internalize these injustices as “good” and “traditional values.” For example, when a woman is raped, the handmaids are forced to recite why God allowed it: “To teach her a lesson.” This raw depiction of rape-culture ideology is another indicator of how the “judges of normality” are guilty of “calling evil good and good evil” (Isaiah 5:20).

The techniques used to uphold the carceral system of The Handmaid’s Tale reflect aspects of a similar carceral system at work in American history. Like the African Americans who were bought and sold as chattel slaves in America, the handmaids are reduced to their bodies, even given painful physical markings to signify their objectification: the slaves were branded and the handmaids given ear tags. Offred says “we are containers” and “two-legged wombs.” The handmaids’ only value is in their usefulness.

Women in Gilead are infantilized and forced to take the name of their oppressors, just as Africans of both genders were in America. Both groups were forbidden to read even the Bible—but it is read to them by those in power; the narratives within were twisted in order to fit the ideology of the regime and justify their cruel means to power. This religious abuse, using the name of Christ in an attempt to erase the Imago Dei, is one of the worst stains on American history—and Atwood warns us against it.

Of course, dissimilar to American chattel slavery, the handmaids’ bodies are cherished as “sacred vessels.” But this is merely another form of objectification. What should be the conception of the Imago Dei within these women is marred in an attempt to destroy it. There is no individual identity in Gilead. These “chosen” women are only “sacred” because they empower the existing authorities by providing them with children, the most important social marker.

In a secret evening meeting, Commander Fred tells Offred: “I only wanted to make the world better,” going on to explain, “Better never means better for everyone. It always means worse for some.” Fred is verbalizing the idea that “there is no empire without slavery.” We see this means of carceral oppression both in world history and American history.

The Handmaid’s Tale has sometimes been pigeonholed as liberal propaganda, but its dark parable reflects fears vocalized from both sides of the American political spectrum. The show and novel have been in the news lately, with women in the handmaids’ archaic garb protesting the Alabama abortion law as a political move that will strip women of ownership over their bodies. The series does warn against a woman losing control of her own body, but the main focus is not loss of rights over illegality of abortions. The central focus of the story, rather, is the pain of losing a child. The handmaids’ bodies are controlled by men through systemic injustice and rape, but the trauma is magnified when their children are taken away. In the American slave era, it was the norm for women to be separated from their children, and in the oft-unspoken Baby Scoop Era of the 1950s and 60s, young pregnant women could be forced to give up their children for adoption. In the present, migrant children are ripped from their families at the border. At its core, The Handmaid’s Tale communicates how ignoring the Imago Dei in another human being always leads to cruelty and brutality. These acts of cruelty also dehumanize the abusers.

The series also explores the death of free speech and the suspicion of science, two intense points of contention in American politics today. In Gilead, the handmaids walk past hanging male bodies near the river in their town. These bodies, faces covered, are reminders that the freedom to speak and act must be restrained at the price of death. These men were professors, journalists, doctors, educators—all heretical professions in Gilead. We learn the Boston Globe headquarters became a “slaughterhouse,” an emblem of the death of free speech.

The false religion of Gilead is not just a theocracy, but also a theonomy in which the judicial laws of the Old Testament are practiced. There is no grace, and in a strange mix of “eye for an eye” ideology and Sharia law, sins are not “forgiven” without abuse and punishment. In reality, they are not forgiven at all. Instead, there is a fear of true religion. We learn that many churches have been torn down and Baptists are outlawed, as is the hymn “Amazing Grace” (and all its implications). Although Gilead considers itself a religious society, there is no freedom of religion, and anyone with a divergent belief is humiliated, harmed, probably killed. Gilead is loveless. There is no Jesus there.

The leaders of Gilead fear the light of Christian love because their quest for power created a self-serving system. Could this carceral system be instituted in non-fictional America? We know it has in our stained past. As Frederick Douglass described it: “Between the Christianity of this land and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference.” Douglass notes it was not only active evil, but silence that allowed slavery to flourish.

In The Handmaid’s Tale, Offred explains: “Nothing changes instantaneously: in a gradually heating bathtub, you’d be boiled to death before you knew it.” The story is prophetic in its warnings to be watchful for a carceral mechanism to manifest around us. And while there is no indication Atwood or the show’s producers see Christ as the answer to these abuses of power, in truth, He is the only thing that can rehumanize those who have been dehumanized. Forgetting the Imago Dei in others is what leads to Gilead. We must let the scales fall from our eyes because, as Offred warns: “I was asleep before—that is how we let it happen.”