In 2006, when Jamie Tworkowski wrote a story about a friend struggling with addiction and depression, he had no idea he was launching a movement.

A few months after posting his story, Tworkowski launched a nonprofit, To Write Love On Her Arms, to help people deal with depression, depression, mental illness, self-harm and addiction.

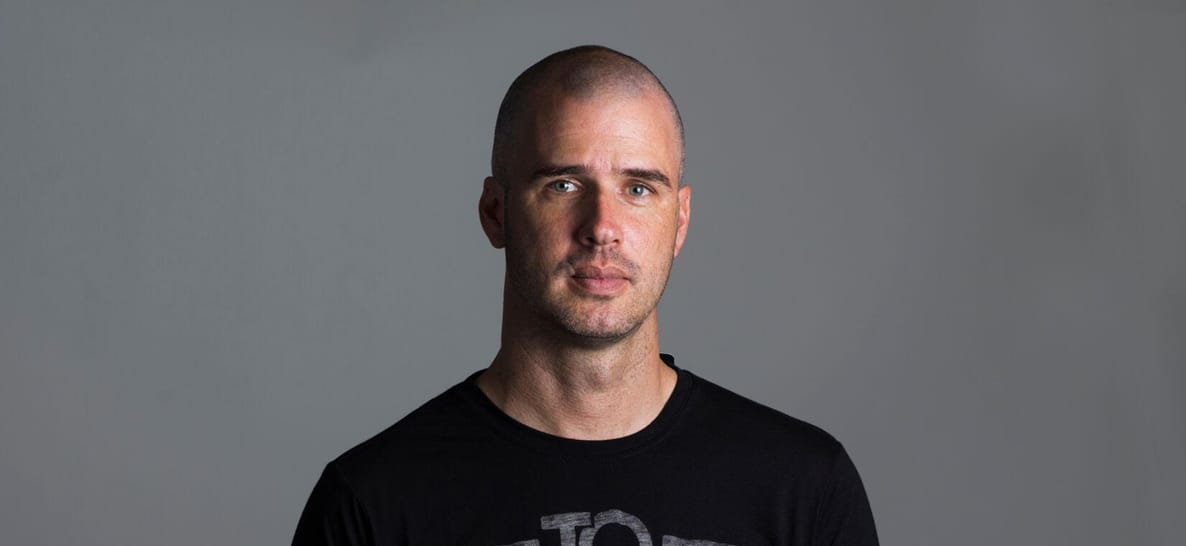

This week, the organization celebrated its 10 year anniversary. We caught up with Tworkowski to talk about the beginnings, what he’s learned and how he’s seen hopeful changes in how the church talks about mental illness.

Congrats on the 10-year anniversary of To Write Love On Her Arms, has it hit you that it’s been a decade that you’ve been doing this?

It’s wild. In some ways, it’s gone by really fast and in other ways I’m aware that a lot has happened. I do think an important place to start is to note that the first TWLOHA T-shirt was designed at RELEVANT, so maybe in some legal realm you actually own this whole thing.

Tell us about the early history. How did this get started back in 2006?

At the time, I was working as a sales rep for Hurley. I was part of a church community in Orlando. I was introduced to a girl who became my friend—her name is Renee, she’s still my friend today. When I met her, she was dealing with drug addiction, depression, self injury. She had attempted suicide. She was denied entry into a local treatment center and spent the next five days living at the house where I was living. We just kept her safe and did our best to keep food on the table and make her smile, and then we got her into treatment.

I wrote a story about the experience and then had the idea to help pay for her treatment by selling some T-shirts. I think I maybe ordered 100 and that felt ambitious. Jon Foreman from Switchfoot was the first one to wear one of those shirts and it ended up obviously taking on a life of its own and becoming bigger. We realized that Renee’s story represented a lot of different people all over the world who could relate to pain, whether it was theirs or someone they had lost or someone they cared about. I didn’t mean to start a charity and I didn’t expect to be working on it 10 years later.

What made you realize it was way bigger than just a project to help a friend? What was that transition like?

It was a whole range of emotions. Obviously, a lot of it was positive, a lot of it was really exciting, but part of it was really scary and overwhelming. I was being asked questions I didn’t have answers to. People were sharing really painful parts of their stories and opening up about things they had never talked about. It just began to snowball. Basically, the story took on a life of its own. People responded in writing. People responded with comments and messages and emails and then the T-shirts very much did the same.

We realized quickly we were in a position to do more than just pay for Renee’s treatment. A couple months later, I quit that Hurley job. I felt like I was being given this really unique opportunity that was hard to explain. I couldn’t know if it would last six months or a year, but it felt like I could bring my heart to work and maybe some people could end up getting help maybe even staying alive. It felt like something that was worth rolling the dice on.

We kind of had a backward beginning because I feel like so many people have an idea, they have a dream, they have a mission, but they don’t have any money coming in and they certainly don’t have an audience. We somehow had money coming in through T-shirt sales. We had a growing audience, obviously, it started small before we ever called it a charity or even thought about that.

So, when you realized it was no longer just about Renee, what was it tangibly about for you in that next season?

There was definitely the sense that it was still a big surprise, it was still a bit overwhelming. I mean, there’s the question of quitting my job, but then there’s also the question of how the heck do you start a nonprofit? How do you run a nonprofit? What’s a budget? What’s a board of directors?

But I think what allowed us to think in that direction was just seeing that so many people were touched by not just Renee’s story but the issues that were represented there. So many people were dealing with the same things. Renee was sort of the catalyst or the first example that made it safe for people to be honest. [I quickly realized] there was such a bigger conversation to be had.

Really, it’s so many of the same ideas over and over again. So now you’re telling not just one person that it’s OK to get help, but eventually, thousands and thousands of individuals. You’re pointing them to honesty, to community, to the idea that they are loved, to the idea that they don’t have to hide, that it’s OK to go to counseling, it’s OK to go to treatment. Really, it’s just kind of duplicating that over and over again in a lot of different settings—different platforms and different mediums but so much of the message has stayed the same.

To specifically answer your question, I think it was just realizing that there were so many Renees out there and the things we wanted to be true for her we now hope they can be true for all these other folks.

To Write Love is much broader than the church world, but it started from the church world. Why do you think the church has been so bad acknowledging mental health and addiction issues?

I think it’s true within the church and outside the church. I think that stigma really exists everywhere that people aren’t sure if it’s OK to go there. I sort of grew up with this sense that to be a Christian meant we were supposed to have it all together and you used words like “joy” and “blessed.” I didn’t really see examples of brokenness or where there was space for brokenness.

I think we do get to see a lot of evidence of change, a lot of positive change. Sometimes it comes at a cost. I mean, Rick and Kay Warren [who lost their son Matthew to suicide] are an incredible example of choosing to use their platform, their audience, their voice to say, “Hey, this conversation needs to be had. This is not a secret. This is not something we’re ashamed of. We loved our son we did everything we could for him to get help. This is how hard it is.”

That story represents the reality of these issues for so many people within the church, within church leadership, and certainly outside the church, as well. There are reasons to hope and to feel like there are a lot of churches that are starting to get it right. Whether it’s mental health or whether it’s something like celebrate recovery. There are a lot of churches that are kind of bringing this out of the shadows.