For centuries in the West, Christians were leaders in the art world, commissioning plays, visual art and music from talented artists.

Name just about any artist you learned about in high school or college, and he or she probably took strong influence from Christianity. Somehow, we went from definitive, groundbreaking art (think the Sistine Chapel) to today’s “Christian art” (think posters in Christian bookstores).

Art created under the “Christian” label often either mimics some form of “secular” media or relies heavily on a simplistic modes of storytelling to get a point across. In this scenario, Christians view artistic pursuits as practical tools that, given the right formula, can directly communicate a message. Many times, the motives are valid and good. But the harder we try to make “Christian” art that explicitly spells out a moral, the more the task appears evasive.

Because of this, “Christian art” arrives too often at sentimentality rather than depth. Sentimentality tries to evoke the cheapest form of an emotion with the least amount of effort, and this is not enough. We have to go deeper, get messier and tell stories better. As N.T. Wright points out in his book Simply Christian: Why Christianity Makes Sense, “The arts are not the pretty but irrelevant bits around the border of reality. They are the highways into the center of a reality which cannot be glimpsed, let alone grasped, any other way.”

The center of reality is a God who is Creator. And since we are made in His image (Genesis 1), we too are creators, able to harness the necessary and practical aspects to make something into something new. In creating good art, we are allowed to mimic the one who created all things—the One who built a universe and said “it is good.” So we create because we were created. As Madeleine L’Engle says, “All true art is incarnational, and therefore ‘religious.’”

This doesn’t mean that every created thing is good or slots itself neatly into the Gospel. L’Engle points out that if we are truly creating art as an overflow of our own hearts and minds, it will reflect the very thing we worship. We see this in society’s representations of success and in the media that it produces.

As Christians, we must ask ourselves: When we create, are we truly engaging in an act of worship that mirrors that which the living God has created, or are we just mimicking the things that which society has cobbled together?

When we look to the Word of God, we see that God inspires storytelling and art. An enormous percentage of the Bible, particularly the Old Testament, is written in detailed poetry. David was a musician and a poet, writing song after song to God in the Psalms in order to express the widest range of human emotion. Jesus didn’t even start the ministry that was detailed in the Gospels until the age of 30—before that, He was known as “the builder,” or “the builder’s son.” He didn’t gain fame or fortune—He worked with His hands.

The Scriptures, though clear about the most important aspects of our faith, do not always offer easy solutions for life’s hardest questions. God sent His prophets symbolic dreams, and Jesus told stories in extended metaphor. The very name for God’s people—the people into which the Church is grafted—is Israel, which means “he struggles with God.” The art of the Bible is not “family-friendly” or simple. It’s apparently OK to create art that doesn’t tie everything up into a neat bow, art that only arrives at redemption after a long struggle.

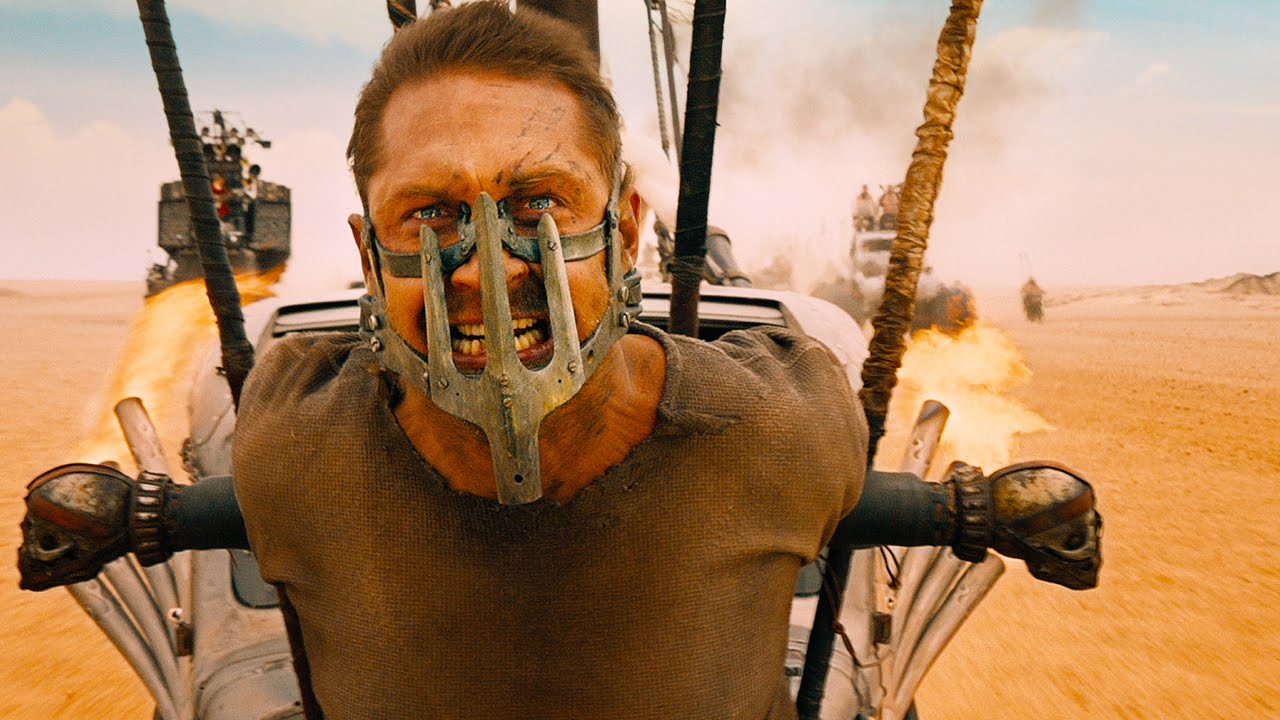

Even though they are not “Christian” stories—or necessarily stories about Christians—there are hints of the Gospel in the image of Mad Max, pierced through both hands, giving his blood to save a life. There are echoes of the struggle in the Psalms in the music of Typhoon. Dostoevsky, Caravaggio, Donne, Bach—they all created art out of this struggle that defies specific pigeonholes.

The creation of art, for the Christian, is a genuine calling and gifting that should not be trivialized. In Exodus 31, God chooses “Bezalel… and I have filled him with the Spirit of God in skill, in understanding, in knowledge, and in all kinds of craftsmanship … I have given ability to all the specially skilled.” A functional temple was not sufficient to house God’s glory; the tabernacle was also made intricate and beautiful.

God gives us the ability to make art, but art that is put to His use. God fills the workers in Exodus with the Holy Spirit to create the tabernacle and the ark, and we should model our own art off of this inspired act of creation. Art created by Christians should do what Bezalel did: create a space in which individuals can meet with God. Art is incarnational on both sides of production and reception. Like Noah’s ark, too, true art takes on a life of its own that is completely outside the hands of the creator—a life imbued by God.

It’s a tall order, but we cannot be satisfied with anything less.