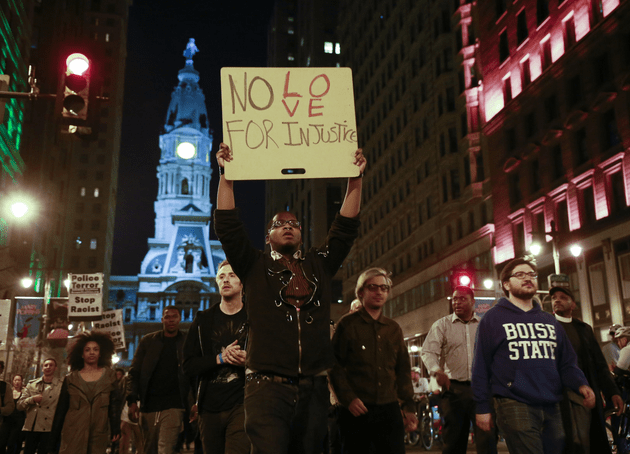

Last night, a jury in Missouri decided not to indict officer Darren Wilson for the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson. The decision set off intensified protests in the St. Louis area and prompted marches and rallies in cities around the country.

We asked Lisa Sharon Harper, the senior director of mobilizing for Sojourners, to answer a few questions about the verdict, the broader context behind the protests and what it all means for Christians.

Why do you think it took so long for the grand jury in Ferguson to make a decision?

In an interview with the Washington Post, Ed Magee, spokesman for county prosecutor Robert McCulloch, said of the normal St. Louis grand jury process: “Normally they hear from a detective or a main witness or two. That’s it…” The Associated Press reported that a normal grand jury case is usually heard within the course of a single day. This one took three months. McCulloch decided to conduct the grand jury proceedings as if it was the actual trial, offering all of the evidence without recommendation for what charges the prosecutor recommended to the jury. That’s a lot of information for everyday citizens to sift through and an extremely high legal learning curve. I think that’s why it took so long.

For people, particularly Christians, who see this outcome as the wrong decision by the grand jury, what is the proper way to express their disappointment and feelings that an injustice has taken place?

Violence is never appropriate, but there are a myriad of expressions of grief, righteous indignation and holy anger in Scripture. Nehemiah drops to his knees, weeps, fasts and prays. Jeremiah weeps and cries out and calls the powers to account. Moses confronts the powers with four words God gives him to say: “Let my people go.” Jesus puts holy rage on full display in the Temple. He turns over the tables and confronts the Pharisees who are actively calling the people to abide by oppressive economic system. He calls them a brood of vipers. Anger is appropriate. Weeping is appropriate. Creative public witness is appropriate.

Many millennials, who are now a generation removed from the civil rights era, haven’t experienced a case like this that uncovers so many old wounds stemming from racial injustice. Can you help put this case, and other recent stories of police violence against black men, into a greater context?

I believe what we are witnessing is the natural product of a fundamental sin and sickness that has woven its way through more than 300 years of history in the U.S.

Consider this: Before the mid 1600s, slavery in the U.S. was not in perpetuity and it was not race-based. It was indentured servitude, a system where men and women worked off debt for a finite time. In the mid-1600s that changed with the shift to attach the state of servitude to race (blackness, to be exact) and to transform it into a condition that would last in perpetuity. From that point forward, to be black in America was synonymous with being less than human—legally chattel—things—that were owned. Now imagine the psychological impact of seeing black women, men and children walking through the town square in chains, confined and controlled on individual plantations, having absolutely no agency over their lives or their families, or their own land—for more than 250 years. This is the way criminals were treated in Europe. After seeing black people in this state for more than 12 generations, what is the belief you start to take in about the natural state of black people? They are inherently criminals.

Meanwhile, the 1790 Naturalization Act established the supremacy of whiteness by saying only whites could become naturalized citizens. For more than a century, you then see case after case brought to the supreme court arguing that a particular ethnic group is “white.”

After the Civil War, blacks thrive for about 10 years. They vote and run for office and fill the courts with judges and state houses with representatives, senators, and even Lieutenant Governors. Then, suddenly, federal troops pull out of the South and vigilante “justice” becomes the norm. For the KKK, which traces its origins to this era, justice was the restoration of the white man to ultimate power. So, for 90 years, black men, women and children are lynched—killed—for the slightest infraction. They look a white woman in the eye, or fail to step off the curb when a white person passes by, or drink from the white water fountain, or—God forbid—register to vote, and their bodies would be swinging from a tree soon after. Hanging was a penalty for criminality in Europe. During the Jim Crow era, it was applied to black people for any act, or hint of an act, that questioned the power and supremacy of whiteness.

Then the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act was passed and with them came Federal enforcement of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, which promised blacks and all citizens equal protection under the law and equal access to the voting booth. Then, the “Tough on Crime” movement rose up in the 1980s and 90s, and lowered the bar of criminality. It called for drug possession to be considered a criminal offense for the first time in U.S. history, In addition, it called for exorbitant mandatory minimum sentences. Then, even though whites do drugs at the same rate as black people, local governments concentrated their federally backed “drug war” policing efforts within black and brown communities,. Within 30 years, the prison population grew from 500,000 in 1980 to 2.2 million in 2010. Today, more black men have some interaction with the criminal justice system than were slaves in 1850, according to Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow.

What does this have to do with Ferguson, a millennial might ask? Everything.

What is the effect of more than 350 years of viewing black people as less than human and inherently criminal? What is the effect of more than 350 years of policing and criminal justice structures constructed with that fundamental belief woven into their foundations? It is only natural then, that in Ferguson and in many small towns across the country where the unconscious beliefs about the value of black life are still prevalent, a white officer can shoot a black boy or man and legally get away with it. We crafted the system over 350 years to work that way.

Ferguson has had a disproportionate amount of white individuals in authority positions compared to the overall population demographics. How can we help to make local governments more balanced in under-represented communities?

Join national and local efforts to restore full voting rights to marginalized people groups, especially citizens returned from incarceration. In many states, their right to vote has been revoked as part of the “Tough on Crime” movement. The effect is the permanent exclusion of millions of citizens from the right and ability to exercise agency over their communities—even after they have paid their debt to society.

For months, the shooting of Michael Brown has ignited conversations around the country and on social media. From what you’ve seen, what has been encouraging to see in these conversations, and what has been disappointing?

Last night, #Evangelicals4Justice, an eclectic group of evangelical thought leaders, held a Twitter teach-in one hour after the grand jury announced its decision in the Darren Wilson case. Read the hashtag feed. It’s powerful. Evangelicals leaders, seminarians, young people, activists, moms and teachers logged on and reflected from the heart and the mind why “Black Lives Matter.” It was like nothing I’ve ever seen before. From the grassroots to the leadership, evangelicals reflected on the theological, sociological and moral call to affirm the image of God—the inherent human dignity in all life, including black life. Led by the cries and demands of the young black leaders of the Ferguson movement, a national conversation has begun and we are a part of it. That was encouraging.

This case has put a spotlight on racial tensions that still exist in many communities. How can individual Christians be instruments of healing of and reconciliation?

Three things:

1) Acknowledge and affirm the image of God within the people who live in the “Fergusons” of your city.

2) With that acknowledgement we must also acknowledge and affirm that to be made in the image of God is to be made with the capacity to lead. In fact, Isaiah 61 promises that it is the oppressed, the marginalized, the weeping ones, the imprisoned, who will be the ones to restore the devastations of many generations. The promise of Scripture is that it is the people of Ferguson who will do it. Not the affluent church. So, as we engage, we must enter with a posture of humility—a learning posture—in submission to the leadership of the indigenous leaders of the movement. We must acknowledge that they know the issues better than anyone. They have borne them on their backs for their whole lives. And part of our societies restoration comes in the rediscovery of the marginalized ones’ capacity to lead.

3) Finally, we must be shrewd. Whiteness has privileges and power in our nation. The call is not to rid yourself of that privilege. That is impossible. You did nothing to deserve it. You cannot get rid of it. White privilege is bestowed by society, not earned. So, leverage it—in partnership with the dreams of the ones God says will become his Oaks of Righteousness (Justice).

The Church itself is a powerful social force in many communities. What kind of programs and ministries should we be focusing more on that can effect positive social change?

For the Church to engage the whole life of its parishioners, it must engage the whole community those parishioners live in; not only its immediate neighborhood, but also its surrounding city and state context. The whole life of parishioners includes not only how systems, structures, and culture affects the daily lives of the people sitting in our particular pews, but also how our relationship to those outside of our community affects them. Are we actively loving the “other” with our hands, our feet, our hearts, our minds and our votes?

Most churches today have a category for small group ministry to minister to the individual growth needs of the people in the church. They have a category for compassionate ministries that minister to the felt needs of the less fortunate in their neighborhoods. What we need now is the development of justice ministries that examine how local governing systems and structures impact churches in marginalized communities. We need justice ministries that leverage the power of affluence in partnership with the Oaks of Righteousness on the other side of the highways.