“We always look for connections.”

That’s what the Muslim imam tells me and my fellow travelers when we ask how it is he can partner with a Christian organization. We’ve been in Sri Lanka a week. We’ve gotten the lay of the land. And we’d all been amazed at how well the various religions of Sri Lanka—Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim and Christian—got along. It’s even more amazing considering Sri Lanka is just two years removed from a 20-year armed rebellion by the Tamil Tigers.

Joffrey, the imam, is 26. He’s been away to school and come back to serve as the imam of the mosque in his home village of Willuwa. He met every question we asked with a smile, even a laugh—far from the image of the stern, severe imam I hold in my head, a product of American television. He’s a happy guy, especially when holding his 20-day-old son.

“Christians and Muslims have a hard time getting along in the States,” I say to him through a translator. “Do you have any advice for us?” In response, he reiterates his exhortation that we look for connections, always look for connections. He makes it seem so easy when he says it.

We left his house and went from visiting one of the youngest clerics in the district to one of the oldest—and most respected. Venerable Horagolie Dhammika Thero arrived in Willuwa in 1964 and set up shop as an Ayurvedic healer and Buddhist monk. When we arrive at his temple, he is busy giving someone an herbal treatment.

Just as we had with the imam, we remove our shoes before taking seats on his porch. We are advised to sit at a lower level than him. We thank him for taking the time to meet with us and ask him how he came to be in Willuwa.

“My father was an Ayurvedic healer,” he tells us, “as were the men of many generations in my family. I wanted to be a monk as well. So I am both.”

“When I came to Willuwa, there were just 17 families,” he says. Joffrey was 11 when he first became involved in a local child society started by Christian aid organization World Vision. It was there he first started interacting with—and playing with—children from other faiths.

“My temple was one small, mud hut,” he continues. “There was also a Catholic priest, and his church was also a small mud hut. Many times, when I needed to go to town, he would pick me up on his bicycle and we would ride together.”

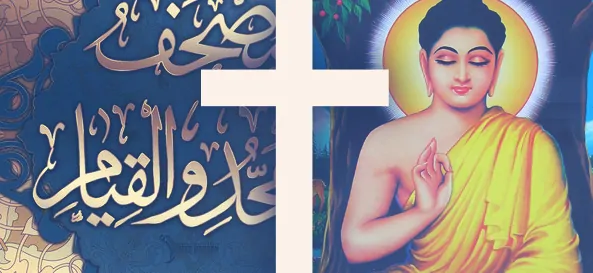

This image—a Buddhist monk riding on the back of a Catholic priest’s bike—has stuck with me. It’s an image of cooperation that we, in the United States, are sorely lacking. Sure, there are official interfaith dialogue sessions, and we’ve all seen priests, pastors and imams sitting together and playing nice at inaugurations and state funerals.

But let’s be honest. American Christians are pretty much terrible at true, deep cooperation with those of other religions. Our leaders talk about Islam being a “religion of peace,” but we get the sense that they don’t quite believe it, that they’re hedging their bets.

What I heard from Imam Joffrey and Venerable Horagolie Dhammika Thero transcends the interfaith conversations and the “respect” that we tout in the States. I sat directly behind the two of them at a World Vision ceremony, and I watched the old monk and the young imam lean over and talk to one another, laugh at one another’s jokes, applaud one another’s dancers.

This wasn’t grudging respect for another religion. This was friendship. The monk and the imam—and, for that matter, the Christian World Vision worker—genuinely know one another.

That’s not all that happened while I was in Sri Lanka. Buddhist children bow down and touch their foreheads to my feet, and local Christian aid workers pay the same respect to Buddhist monks. I receive a blessing from a Hindu priest that includes a mark on my forehead that I wear the rest of the day. I witness a Hindu fire-walking ceremony, and I serve communion to Catholics.

It’s unrealistic to think Christianity is going to make major inroads in Sri Lanka, a country that is officially Buddhist and in which Christians make up only 0.6 percent of the population. But some will wonder about the “witness” of these Christian workers or about whether I “shared the Gospel” on the trip.

Of course, we have heard and repeated the (dubitable) St. Francis trope about preaching with words if necessary. But larger questions loom: What does it mean to share the Gospel through actions in a country in which Christianity is the fourth religion? What does it mean for a Christian relief worker to receive a Hindu blessing or to prostrate herself at the feet of a Buddhist monk? How do you serve in a country that remembers 400 years of forced conversions by Christian missionaries?

What I think it means is a different way of thinking about the Gospel than we’re used to. It means acknowledging the Gospel is a lot bigger than saying a “sinner’s prayer.” It means Christian identity in a pluralistic society—especially one in which Christianity is in the minority—is not a weapon. It’s a jewel, a precious jewel to be cared for, protected and displayed with pride. But like a truly precious jewel, it’s not likely to be reproduced in large quantities.

The Christians of Sri Lanka taught me a great deal about this, as did a Muslim imam and a Buddhist monk and a Hindu priest.