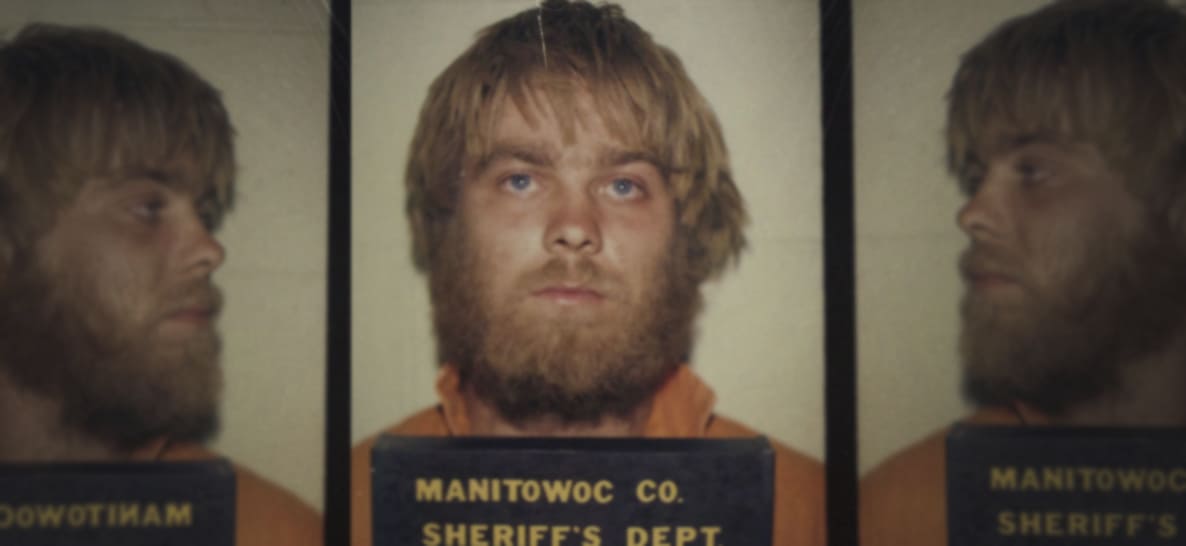

Few shows have taken the Internet by storm like Making a Murderer, Netflix’s true crime documentary about Steven Avery’s murder trial. In the wake of the show’s exploding popularity, hundreds of thousands signed a petition asking President Obama to pardon Avery, and Avery has filed new appeals for retrial.

But Making a Murderer is just the latest in a string of extremely popular true crime shows, including the Serial podcast and the upcoming show American Crime Story, which will portray a dramatized version of the O.J. Simpson trial.

We talked to Russell Moore, president of the Southern Baptist Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission, about why true crime stories have made a resurgence, and what Christians should make of them.

Why is it that true crime shows are having a cultural moment right now?

I think there are several reasons: One, there’s always a human fascination with crime and punishment. There’s a fascination with seeing how evil things are resolved. I think that’s rooted in a human longing for justice and really wanting to see a sense of control of the universe around us. [It goes] back to the classic problem we see so often in Scripture: “Why do the wicked flourish?” Many of these programs help us get a sense of justice being done or being ignored and how can that be made right. It hits at the core of who we are in the image of God.

Also I think, culturally, there’s a sense of paranoia and a sense of distrust of institutions that shows up. Some of that is rightly earned and some of that is maybe not. But we see so many things—from the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009 in which we had big corporations making really unsavory decisions that were invisible to most people behind closed doors, to some of the abuses within the criminal justice system that we see from the Trayvon Martin case and beyond.

These programs are emphasizing the possibility of conspiracy and ambiguity in a way that older sorts of mysteries didn’t do. You think of Serial, for instance, and Making A Murderer. When Serial was going on, we would have, on my own team, arguments constantly about whether Adnan Syed was guilty or innocent. And the same thing is happening right now about Steven Avery. But there’s no resolution at the end. There’s still a sense of ambiguity so you can have that ongoing argument. I think that fits with the times.

We’re seeing some visceral reactions particularly to Making A Murderer—to the perceived injustices in the Avery case. Can you talk about the spiritual aspects of these cries for justice that are happening as we watch these stories unfold?

Even when I disagree with these loud cries for justice, I’m encouraged by them—really on either side. When one sees people saying, for instance, “Making A Murderer doesn’t get it right, because they did not include all of the evidence that was marshaled against Steven Avery,” or when you see people pointing to the real deficiencies in legal representation of Steven Avery—in both of those cases, you’re seeing an objective standard of justice in a fallen world in which there are often great ambiguities.

So I think the reactions to Serial and Making A Murderer really do away with any sense of true relativism, because if the police planted evidence, that’s wicked. If Steven Avery raped, tortured and murdered this woman, that’s wicked. We can all agree on that. It seems to me we almost have in Serial and in Making A Murderer and in other similar programs—even where there’s disagreement—there’s a common baseline of a moral order.

Is there a danger to these shows?

There is a danger with programs such as Serial or Making A Murderer, because they’re packaged as entertainment media. We can sometimes find ourselves dehumanizing the people involved.

I remember when the first season of Serial was at its high point that Best Buy put out a tweet referencing something about the pay phone at Best Buy—where one of the calls was supposed to have been made—in kind of a joking way. At first, I thought this was good sport for Best Buy and then I realized, wait a minute, this is talking about a young woman who was murdered. This is dealing with real people. So I do think there’s a danger. Just as these programs can help engage people in some these questions, it can also harden us and make us callous toward human suffering, if we’re not careful.

Of course, when we watch shows like Making a Murderer or listen shows like Serial, we do so as Christians. And, as you’re saying, they bring up important issues of justice. In your opinion, has the Church done an adequate job of taking up these kind of justice causes?

No. I think there have been voices in the Church that have called us to a Christ-centered engagement with these issues. I think, for instance, of Chuck Colson, who did more than any other man in the last probably 100 years in American life in calling the Church to remember prisoners and to think about implications of the justice system. But I don’t think we’ve thought about those things adequately.

For instance, look at some of the radically different ways that white and black evangelicals will view the same cases during the whole variety of cases we’ve seen just in the past couple of years.

What I hope is the benefit of programs such as Serial and Making a Murderer is that we begin to get a sense of empathy for victims and victims’ families and also for those who do find themselves in a criminal justice system where the deck is stacked against them.

I think Steven Avery is a murderer, based upon not only the program, but based upon the evidence I’ve read about since then. But I can also see in watching, for instance, a real injustice in the way the court-ordered defense attorney handled the confession of the Avery nephew. Even though I work on criminal justice system issues all the time, it really caused me to spend a great deal of time thinking about about that person who is falsely accused but doesn’t have the money to have adequate legal representation. That’s something I think we should be thinking more about.

Scripture teaches us to respect those in power. We’re in a cultural moment where more and more people are looking suspiciously at a justice system that seems untrustworthy. So for Christians, where is the line between respecting our authorities and questioning them?

It should be the same as it is for every other creational institution. These institutions and systems are created, but fallen. So we can see genuine authority and we can see a blessing. It’s a blessing to live in a country with a criminal justice system that is as good as the American system of justice is. It’s a blessing to live where the vast majority of people involved in the criminal justice system are doing honorable jobs.

But we also recognize that we’re living in a fallen world, and that means fallen institutions. So we give honor and we give respect but we don’t deify any human institution, which means we’re respectful but questioning of any institution.

The same thing would apply to the Church. We give respect and honor to the leaders God has given to us, but we don’t give unquestioning support to the Church simply because it’s the Church, or to any Church leader simply because he’s a Church leader. That was one of the principles of the Reformation: the Church can err.

Respectful questioning enables us not to be the sort of people who are in a paranoid suspicion of “Our leaders are always out to get us” and to think of authority as wrong, which is an unbiblical and ungodly way of seeing things. But having an understanding of fallenness keeps us from being disappointed.

When we are moved to action by the true crime phenomenon we’re seeing, what can we actually do?

I think it’s multi-pronged. We have to expect political leaders to address issues of criminal justice reform, and that means we take that into account as we’re voting. It also means every Christian who’s a registered voter is at least potentially a juror, so we’re shaping our consciences to be able to come to that task—should we be called upon to do it—with impartiality, with fairness and with a sense of seeking justice for those who are victimized.

The other part is we have to have churches that are ministering to people in the criminal justice system. Prosecutors, defense attorneys, police officers, detectives are often in situations in which they are bearing incalculable burdens. I once was talking to a man who was a Christian and he was a prosecutor of child sex crimes. The spiritual weight that he had to bear was unbelievable. And I’m not sure anyone in his church was able to minister to him in that.

Also, we need to minister to those who are in prison. So to really put into place prison ministries and ministries to prisoner’s families in which we don’t simply forget them when they’re behind bars.