Before we discuss Kendrick Lamar, it’s important to acknowledge there’s nothing we can say he hasn’t already said about himself. Whether you love him or hate him, think he’s rap’s savior or its overhyped poster boy, think he’s the realest rapper out there or a poser, know that Kendrick has already struggled with these thoughts very publicly. On “Ab Soul’s Outro” from 2011’s Section.80, Kendrick grapples with the many seemingly disparate pieces of his personality when he raps “The next time I talk about money, h***, clothes, God and history all in the same sentence, just know I meant it, and you felt it cause you too are searching for answers. I’m not the next pop star, I’m not the next socially aware rapper, I am a human ****ing being.”

That is Kendrick Lamar, and long may he remain so. Ever since his 2012 good kid, MAAD City utterly changed the hip-hop game, the national conversation around him has swirled with questions over who he is and what he means. As an album, good kid, MAAD City was a blistering, searing look at what it meant to grow up in Compton, Calif.—to be, in his own words, Compton’s “human sacrifice.” The gang culture in Compton is fierce—almost inescapable. He felt the pressure to swear fealty to its culture of violence, objectification and drugs. But always, in the back of his mind, the words of his mother resounded, trying to spin his fraying loose ends back together. On a voicemail she leaves him that’s played on the album, you hear a mother’s heart breaking over her wayward son.

“Why are you so angry? I hope you come back and learn from your mistakes. Come back a man… Tell your story to these black and brown kids in Compton… When you do make it, give back with your words of encouragement. And that’s the best way to give back to your city. And I love you, Kendrick.”

The album is a chronicle of a young man reaching the end of his rope, and the faith that was there to bail him out when he got there. In fact, it ends with him praying the Lord’s prayer, asking to “receive Jesus to take control of my life that I may live for Him from this day forth.”

Was the album explicit? Absolutely. Do the depictions of violence and sex seem odd next to the proclamations of faith? Yes, but you can tell they feel as strange to Kendrick as they do to his listeners. He’s trying to sort out the many, many complicated influences on his life, and he’s doing so in a very public forum. On “Swimming Pools,” the chorus may be about drinking “pools full of liquor,” but the verses find him in a furious Gollum/Smeagol-type conversation with his better nature. “Open your mind up and listen to me, Kendrick!” the angel on his shoulder pleads. “I am your conscience! If you do not listen then you will be history, Kendrick!”

This is a long introduction, but it’s important to understand To Pimp a Butterfly in the context of what Kendrick has done before. He’s an incredible talent—one of the two or three most important rappers in the game right now—but he’s far removed from the braggadocio common to the hip-hop scene. On the contrary, Kendrick is very honest about his self-doubt, his fears of failure, and the pull between his faith in God and violence of his upbringing. That might lead some people to call him a hypocrite but then, he’s already beat them to that particular punch.

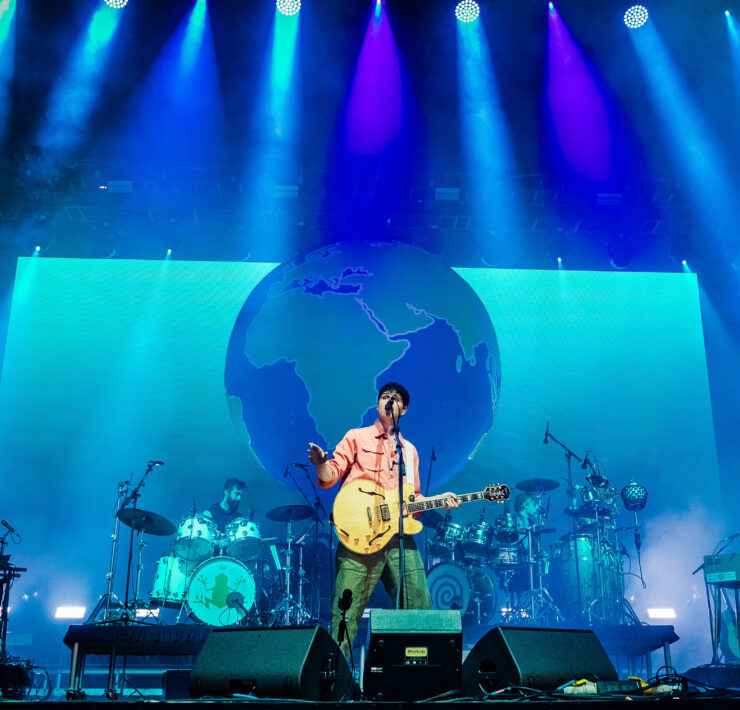

After the lengthy descent into brokenness and hope of good kid, MAAD City, there was really nowhere to go but out, and goodness, did Kendrick ever turn his attention outward for the follow-up. To Pimp a Butterfly is a tremendously dense, complex work that defies any easy categorization. Musically, it’s hip-hop in name only, as its influences careen through a dizzying array of genres, from Miles Davis-type jazz to ’90s g-funk. Even in this sample-leery age, he pulls in everyone from the Isley Brothers to Sufjan. Every track features live instruments, frequently sounding like they’re on the verge of spinning out of control. Just when you start to get a feel for the song, it switches gears on you, generally for wilder territories.

It’s fun to imagine the look on the faces of execs at Interscope Records when they first heard an album this tightly packed—nothing on it was designed to top charts, which is a brave move for a man who can write a red-hot radio hit in his sleep. Even the jaunty first single, “i,” is here stripped down and turned into something leaner and more forceful. When the blistering, ferocious “The Blacker the Berry” first dropped in February, it sounded deliriously heady, so it’s saying something that it actually ended up being one of the most straightforward songs on the album. This is a rich, confounding tapestry of sonic influence, and it’s not half as compex as the lyrics.

Kendrick is acutely aware that he’s become an extremely prominent black man at a time when the conversation about blackness in America has turned volatile. This weighs very, very heavily on him, and nearly every track deals with Kendrick alternately attempting to say something meaningful about race in America while also sorting out his own reasons for why he feels so pressured to do so. “I remember you was conflicted,” he says in a recurring spoken word poem addressed to Tupac Shakur, with whom Kendrick feels a spiritual kinship. “Misusing your influence / Sometimes I did the same / Abusing my power full of resentment / Resentment that turned into a deep depression / Found myself screaming in a hotel room.”

That “screaming in a hotel room” is a scene he addresses in detail on a track called “u,” which the obvious companion to “i.” But where “i” is bright and full of self-empowerment, “u” is supremely unsettling. If you’ve ever wanted to hear a rapper have a nervous breakdown over a swirling storm of jazz instruments and clinking bottles of liquor, you’re in luck. “You ain’t no leader!” he screams at himself, his voice threatening to break. He sounds like he’s crying. He sounds like he’s going insane. It’s bewitching.

The self-reflection runs even deeper on “How Much a Dollar Cost?” which finds Kendrick enjoying his privilege when a homeless man asks him for a dollar. Kendrick refuses, figuring the man will use it to buy drugs.

You looked at me and said, “Your potential is bittersweet” I looked at him and said, “Every nickel is mines to keep.” He looked at me and said, “Know the truth, it’ll set you free: You’re lookin’ at the Messiah, the son of Jehova, the higher power. The choir that spoke the word, the Holy Spirit, the nerve of Nazareth, and I’ll tell you just how much a dollar cost: The price of having a spot in Heaven, embrace your loss, I am God.”

The song ends with Kendrick praying for forgiveness, “Turn this page. Help me change, so right my wrongs.”

None of this is to say Kendrick is bound to be blasting at your next youth group lock-in. Every track here is labeled “explicit,” and earns that many times over. This review is not going to get overly hung up on the amount of profanity on the album, but it is worth noting that there is a lot of it, and that will certainly make many Christian listeners balk. As Lecrae noted in a recent Buzzfeed article, “To mainline Christians, there are certain cultural nuances that are acceptable and not acceptable. And I think for them, Kendrick doesn’t fall in line with that.” Nevertheless, Lecrae was very open about what clearly is a meaningful friendship. “When you’re struggling with your girl or your mom is sick, it’s rare that you find someone that actually wants to talk with you on a real level. Being able to connect with him on spiritual matters is definitely something that I value and appreciate.”

Likewise, we should all be very careful about judging someone who is so clearly struggling with who he is. Just because his struggle happens to be an intensely public one doesn’t mean he deserves any less grace—particularly when he seems so aware of just what people would like to condemn him for, and so bound and determined to upend those expectations.

On the very first track, “Wesley’s Theory,” Kendrick pulls some compelling wizardry—rapping about all manner of appalling behavior on the first verse, only to turn the tables on the second verse, in which fame itself (portrayed as “Uncle Sam”) shows up to encourage the behavior, pushing him down the road to self destruction. Likewise “These Walls” starts off sounding like a sexual ballad, but the metaphor slowly unveils itself as something more paranoid—the fear of falling into complacency and surrendering to his worst impulses.

Those worst impulses are a regular feature on To Pimp a Butterfly, where Kendrick is repeatedly lured by a woman named Lucy—an allusion to Lucifer—who tries to talk him into embracing a life of compromise. He doesn’t seem at all sure that she won’t succeed.

He also tries to find some answers for the question of what it means to be black in America, and just how deep the roots of racism and violence go. His exhaustion is palpable. Indeed, despite being one of the most technically proficient rappers alive, he spends more time here hurling out words like a slam poet, largely ignoring what few beats there are. It’s hard to imagine anyone wanting to dance to much on here anyway. This is more likely to start a conversation than a dance party. In fact, a conversation provides the backbone and exclamation mark to the entire experience.

To Pimp a Butterfly‘s last track features Kendrick in a digitally manufactured conversation with Tupac, as the two discuss their influence and their faith. This neat trick allows Kendrick to pull back the curtain on some of his extended metaphors, and he goes into great detail about his ideas of caterpillars and butterflies, and how they represent his journey from the streets of Compton to a place of celebrity, and back again. It’s a quiet, refreshingly straightforward moment in an album with precious few of them.

This is a big, brainy album, packed with more ideas then could possibly be unpacked in one review, but for now, it’s safe to say that To Pimp a Butterfly is important. It confirms our suspicions about Kendrick: He is one of the most important musicians of his generation. It belongs in the category of huge, musically daring leaps like Radiohead’s Kid A. It’s an uncomfortable, sometimes traumatic exploration of one deeply contemplative soul standing in the center of a maelstrom of ideas, influences, temptations and beliefs, trying to find an anchor. He’s trying to stay true to who he believes himself to be, who he feels called to be and what sort of person he wants to be—and he’s not entirely sure all that is even possible.

Of course, all of that means there are precious few definitive answers on To Pimp a Butterfly, but maybe there don’t need to be. Kendrick is asking some amazing questions.