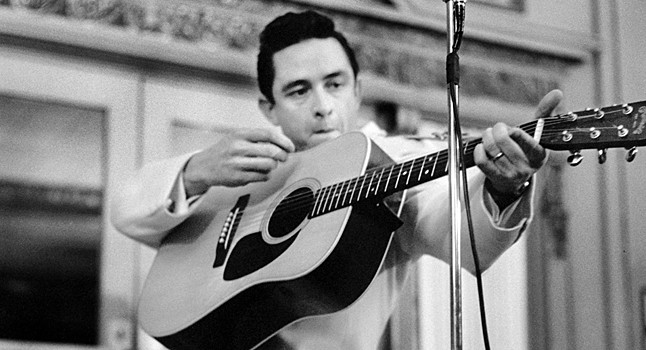

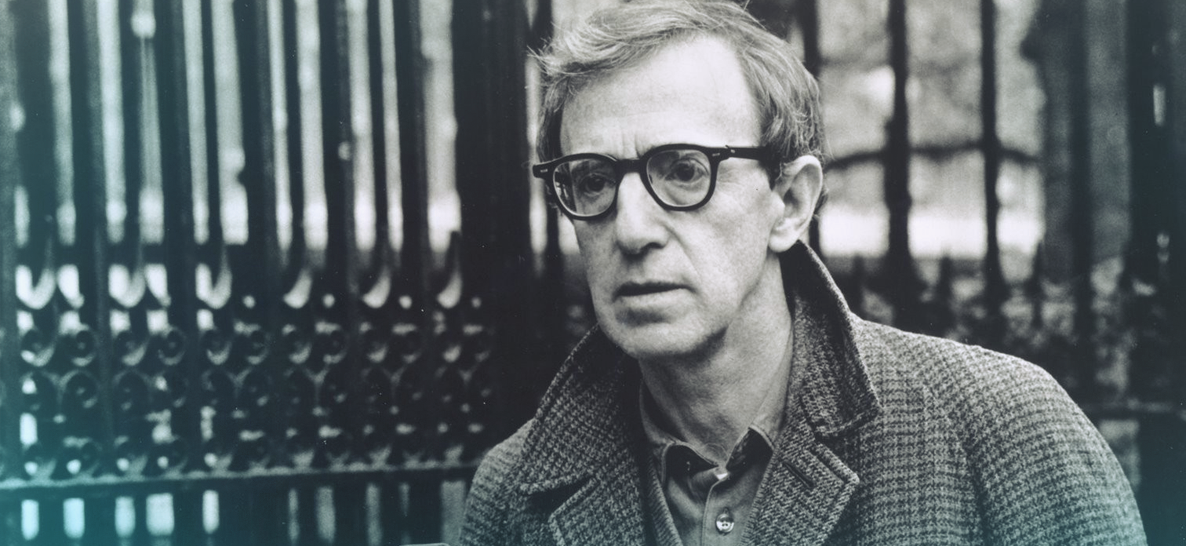

It’s not so much that it’s a shock that Woody Allen was honored at last night’s Golden Globe Awards. He has won four Academy Awards, directed dozens of films, and forged relationships with some of Hollywood’s biggest names.

Midnight in Paris was a recent favorite among the twentysomething set, capturing Allen’s neuroses and the carpe diem attitude that translates so well into films that showcase Owen Wilson wandering the rue de something in the wee hours of the morning.

But what do we do when our favorite movies are made by people whose personal lives reveal them to be not only unlikable, but morally objectionable?

Woody Allen famously split from his then-partner Mia Farrow when she found nude photos of their 20-year-old daughter, Soon-Yi Previn, in his desk drawer. A Vanity Fair profile in 1992 had some very serious allegations detailed Allen’s sexual abuse of Dylan, a daughter he adopted with Farrow:

“She and Daddy went to the attic … and Daddy told her that if she stayed very still he would put her in his movie and take her to Paris. He touched her ‘private part.’” Reporter Maureen Orth, who wrote the original piece in 1992, followed up in November with Dylan, who said “I’m scared of him, his image.”

Yet last night, this man had his praises sung by no lesser actresses than Diane Keaton and Cate Blanchett. He didn’t even show up to the Golden Globes (Allen famously does not attend awards shows), and the applause for his “genius” was riotous.

Allen isn’t the only filmmaker whose treatment of women is questionable. Michael Fassbender, star of last year’s Shame and a supporting actor in 12 Years a Slave, was accused by an ex-girlfriend of having thrown her over a chair, breaking her nose and injuring her leg. Terrence Howard, whose turn in Hustle & Flow earned him an Oscar nod in 2005, has multiple arrests to his name involving violence against women, including ex-wife Michelle Ghent, whose pictures are quite damning.

These aren’t the only men whose history of abhorrent behavior have been brushed aside to make way for their careers. Chris Brown, Mel Gibson, and Josh Brolin have all been accused of domestic violence.

So, what do we do? Do we track the behavior of every actor, gaffer and production assistant? Do we discount the real lives of the people involved in the art we consume and judge them on performance alone? Do we draw a line in the sand, adjusting for this or that until we’ll excuse behavior A and not behavior B?

I don’t know what the exact right answer is here. But I do know that any theory of art appreciation worth its salt will not overlook the character of those involved in making the art. Not too long ago, The New York Times’ Mark Oppenheimer wrote a piece about Christian pacifist theologian John Howard Yoder in which it was revealed that Yoder had “groped many women or pressured them to have physical contact.”

Does this mean we should never read Yoder’s works, including his excellent The Politics of Jesus? Well, it might. While I don’t want to dismiss such important work so quickly, I can’t commend myself to a work of pacifism that didn’t result in peace in the life of the person who wrote it.

Some might argue these situations are different enough as to merit separate consideration. Yoder, after all, was writing as himself. Allen and Fassbender, et al, are creating new worlds, worlds from their own imaginations, worlds that don’t really exist in the same world we occupy.

Except, I would argue, they do. Yoder’s ideals of peace were the purview of a world not yet realized, but he was presenting a specific worldview. With so many other alternatives in the realm of pacifism (Martin Luther King, Jr.; Stanley Hauerwas; Dorothy Day), I would do well to put myself under the tutelage of someone who did not perpetrate violence toward women. Similarly, if I want to see a film that asks questions of a life well lived and addresses fear of death, I might watch A Separation or Being There. I might choose not to give my time and money to films directed by or starring people whose attitudes toward women are so cavalier as to not treat them like real human beings.

A thought exercise here, however painful, is to put yourself in the shoes of Dylan Farrow. (For some of you, having been in her shoes, this will not be too much of a stretch.) If an integral part of our faith is to care for “the least of these” (Matthew 25:40), we must do what we can to consider them first. A young girl being molested by the man she trusted most is one of the “least of these.” A girlfriend beaten and bruised by a man who physically overpowered her, and then being convinced to give up the allegations for fear of ruining his career, is one of the least. We can care for these most vulnerable people in a number of ways, one of which is not lining the wallets of those who have attacked them.

Another option is to observe and enjoy the fruits of their labor thoughtfully and critically. I can’t do background research on the moral lives of everyone in every book, movie and album I want to consume. And if someone did that research on me, they would find plenty of objectionable behavior and bents.

We are all of us twisted one way or another, turning away from goodness toward darkness like ostriches who find solace in hiddenness. So if you do see an Allen film, hear a song by Chris Brown or read a book by John Howard Yoder, there’s no need to rake yourself over the coals. But remember the fullness of the person; don’t give into temptations to idolize. Hollywood does enough of that already, and our golden calves must become smaller and fewer. Love what you love, but remember too that we must love with open eyes.